Thanks to Jeff Kaufman, Alessandro Zulli, and Lennart Justen for reviewing drafts of this post, and to Vanessa Smilansky, Jake Lloyd, and Michael Gomez for wet-lab R&D and processing. We also thank Jake Lloyd, Liam Nokes, Genevieve Speedy, Jules Costello, and Nate Phillips for collecting the samples that make this work possible.

Introduction

Airborne viruses cause enormous harm through seasonal epidemics and pandemics. Yet until recently, the technology to conduct routine broad-spectrum surveillance of respiratory pathogens didn’t exist. Traditional approaches either require knowing what you’re looking for (clinical testing, wastewater PCR) or only catch pathogens after symptoms drive people to seek care (syndromic surveillance), missing early and asymptomatic spread.

At the NAO, we think this gap is particularly concerning because airborne pathogens are among the likeliest candidates to cause a catastrophic stealth pandemic: imagine a purposely engineered pathogen, spreading as quickly as COVID-19 with effects similar to HIV.

How could we improve the detection of novel airborne pathogens? We already run a large-scale wastewater surveillance system, CASPER, but not every pathogen reliably sheds into sewage. Respiratory pathogens are, however, easily detectable in swabs—a swab-based system could therefore close the detection gap, reliably tracking pathogens that would otherwise be missed. Running two fundamentally different systems also means that a would-be attacker would need to evade both.

This is why we created Zephyr, a new detection system based on large-scale nasal swab sampling and metagenomic sequencing. Over the past six months, the Zephyr program has collected more than 10,000 nasal swabs in Boston and detected a broad range of respiratory viruses without targeted enrichment. While Zephyr is still a pilot program, we monitor our data for reportable pathogens and would notify the Massachusetts Department of Public Health of any concerning discovery.

Zephyr enables broad monitoring of respiratory pathogens

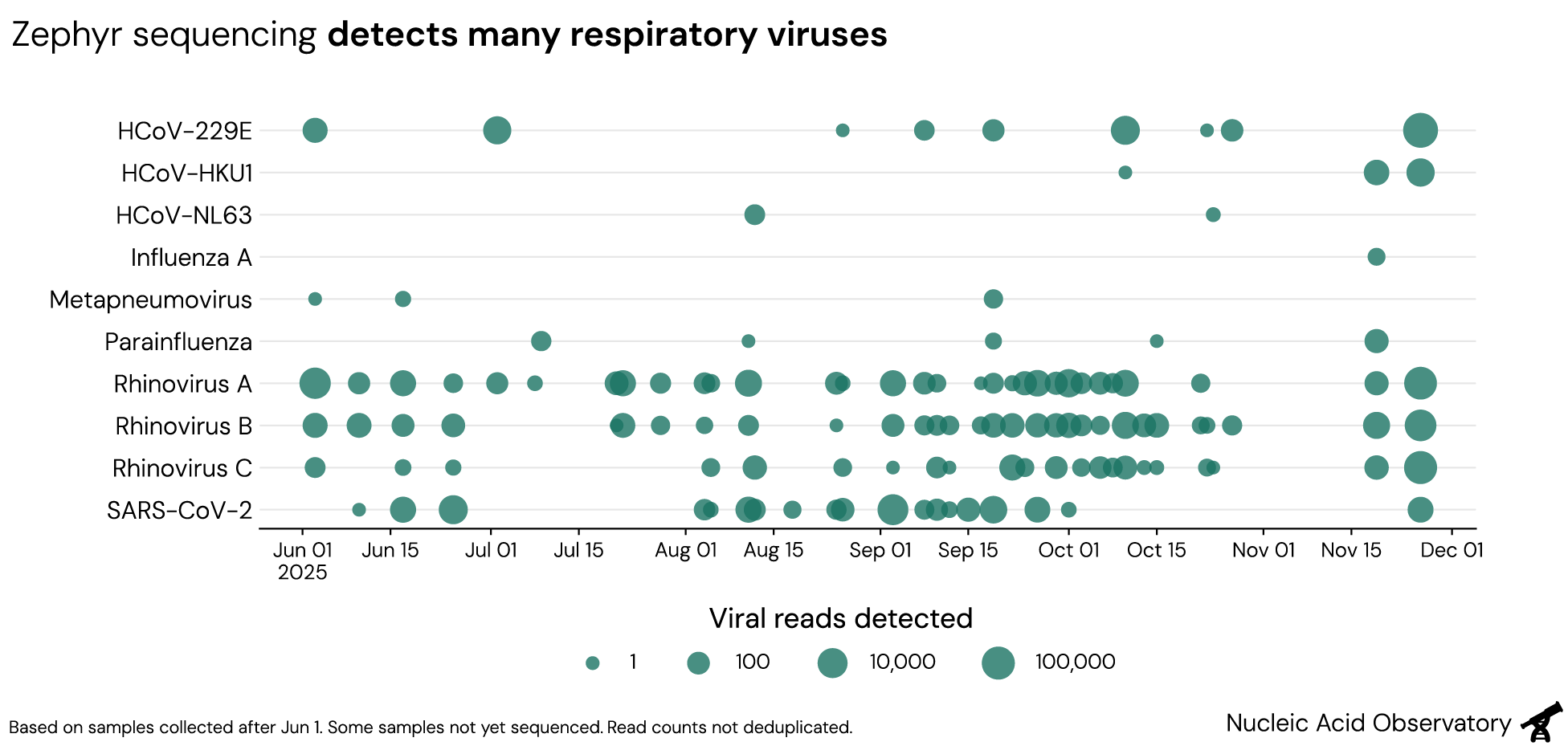

Over the past six months, we sequenced 59 pools of swabs. Across these pools, ranging in size from 29 to 250 swabs, metagenomic sequencing identified a large number of pathogens without applying any targeted enrichment: We have detected common cold viruses like rhinovirus and seasonal coronaviruses, but also pathogens that cause more severe disease including SARS-CoV-2, influenza A, metapneumovirus, and parainfluenza viruses.

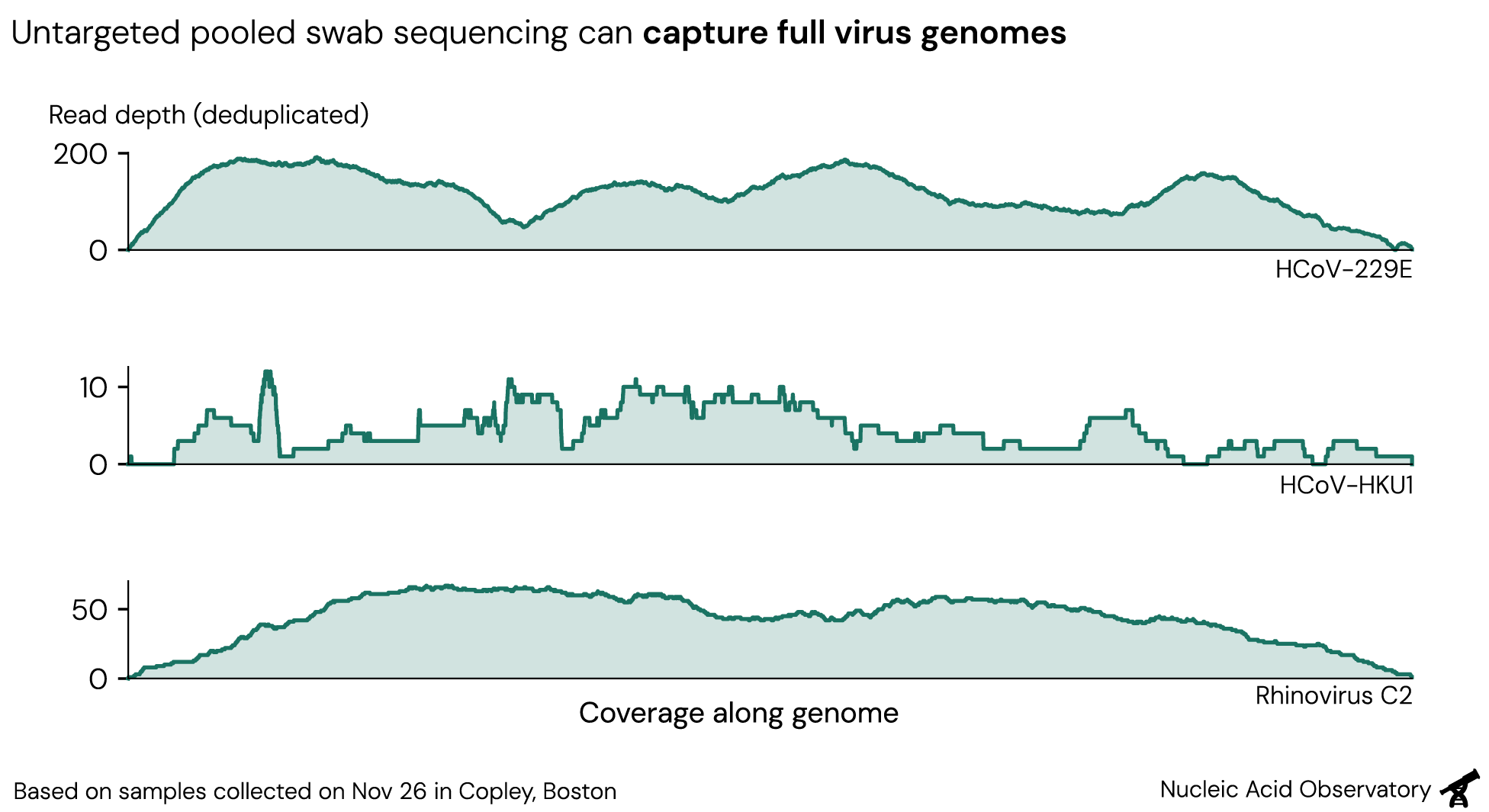

Though we use untargeted sequencing—where any piece of RNA in a given sample can be read out essentially at random—we sometimes recover a full virus genome in a single swab pool. Sequencing samples from Nov 26, we recovered complete virus genomes for HCoV-229E and Rhinovirus C2, and a near-complete genome for HCoV-HKU1. Swabs in this run were grouped into three smaller pools (average 43 swabs each) and sequenced at higher depth than usual. Still, the results show the pathogen monitoring performance achievable with Zephyr.

Recovering whole genomes unlocks several valuable applications. For flagging engineered threats, full genomes enable more robust genetic engineering detection and assembly of pathogens that are genetically distinct from anything previously observed. Public health groups can use the same data for precise taxonomic classification and variant monitoring.

Through the rest of winter, we will continue sampling and sequencing, aiming to generate a dataset that provides the first detailed pathogen-agnostic overview of the respiratory virus season in a major US city.

As part of our pilot, we’ve informed the Massachusetts Department of Public Health of our research activities. If we find any reportable pathogens, we will forward all necessary information, including date, location, and sequencing reads, to the department.

Scaling Zephyr

Nasal swabs are used in healthcare settings across the world, and have previously been shown to detect many respiratory pathogens. To date, no one has used respiratory swabs for ongoing, pathogen-agnostic surveillance of airborne viruses. Initial simulations showing that swab sampling could detect some pathogens at higher sensitivity than wastewater sequencing prompted us to build such a system.

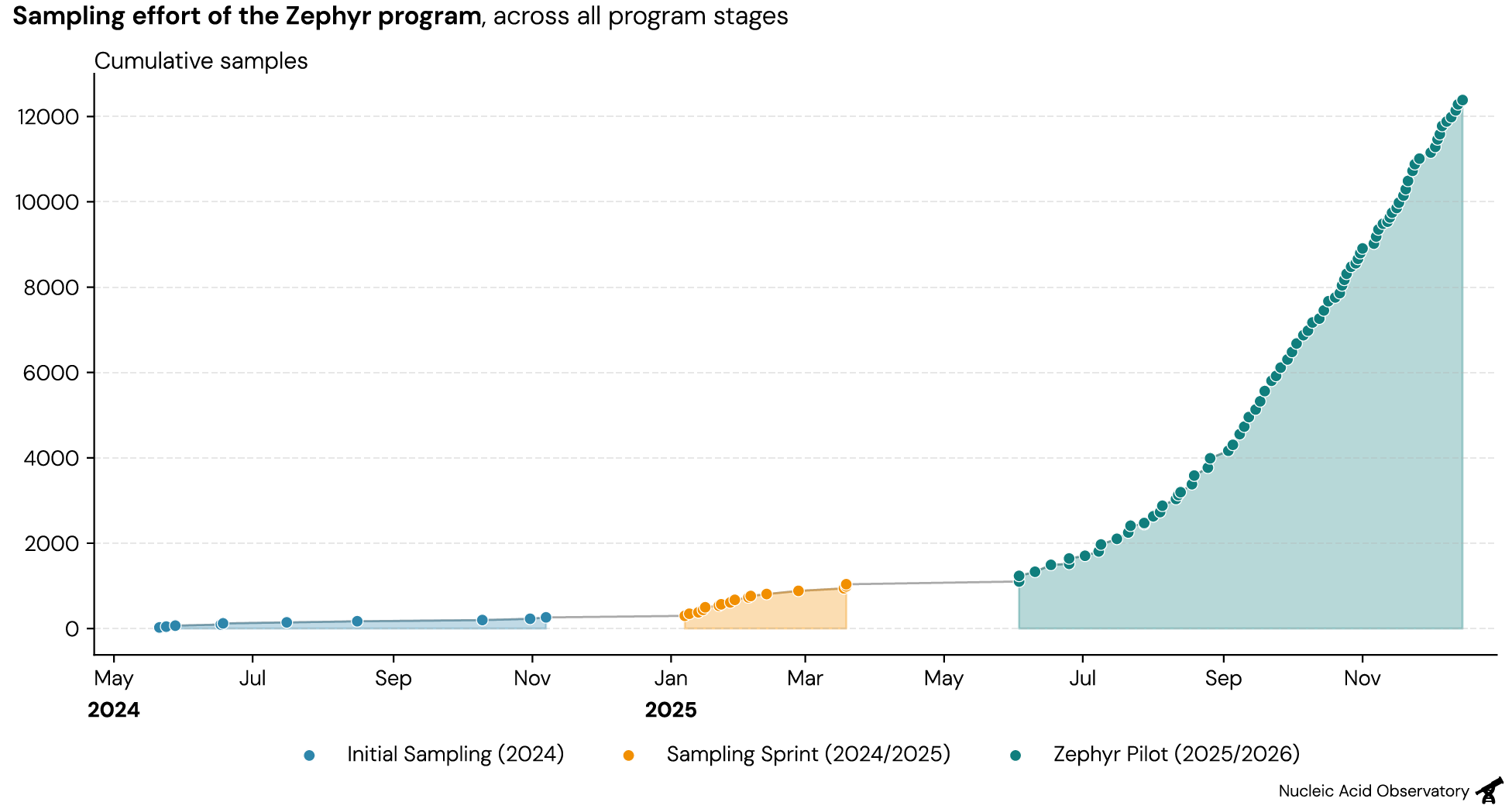

We spent the past 18 months streamlining the collection and processing of respiratory swabs to enable sampling large numbers of people with a small staff. We’ve scaled Zephyr in three stages:

- Initial sampling (2024): Collecting our first samples to design wet lab methods.

- Sampling sprint (2024/2025): As we detected the first viruses with Zephyr, we sampled 1–3 times a week across two months. During this time we found many of the respiratory pathogens you’d expect to see during winter, such as common cold viruses, influenza, SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and others.

- Ongoing large-scale Zephyr pilot (2025/2026): We expanded our collection operation with dedicated staff, both to collect more data and to assess the operational feasibility of running a large-scale sampling program in a major US city.

Today, Zephyr is the NAO’s second biosurveillance system, standing alongside CASPER, our US-wide wastewater monitoring collaboration.

How to sample hundreds of individuals each week

Zephyr has now collected more than 10,000 individual samples over the last six months—an order of magnitude more than all samples we previously collected. This effort is supported by a team of field samplers and an expanded wet lab, who together enable us to sample and process 500–1,000 swabs a week.

To reach this volume of sampling we’ve designed Zephyr to allow highly streamlined recruiting and sample collection, while following the requirements set out in our IRB protocol (#24-08-633-1971):

- Compensation: We provide participants $2 bills, which are unique enough to be interesting to participants, while also being easy to carry and hand out.

- Pooled collection: All swabs are pooled together into one tube upon collection, allowing fast collection with minimal manual handling of samples.

- Anonymous participation: Study participants don’t need to provide any personal information, mitigating privacy concerns and reducing administrative burden.

- Verbal consent: Participants consent verbally after receiving a brochure and any additional information they need, which makes participation very convenient to participants.

Through all these measures, field samplers can achieve collection rates of up to 20–64 samples an hour with only two staff members.

We will keep up our current rate of sampling and processing through the end of the winter infectious disease season (April 2026). The data created along the way will be used both to further evaluate the efficacy of Zephyr and work with local health authorities to identify and flag concerning threats. Additionally, we will be able to link swab sequencing data with our wastewater sequencing data, allowing us to provide far more detailed performance and cost estimates for wastewater surveillance than previously possible.

Building on Zephyr

We want Zephyr to be useful beyond the NAO. To that end, we’re making our data publicly available for surveillance and research, and sharing our methods with organizations that might want to set up similar programs elsewhere.

Data sharing

A growing number of groups are working on pathogen detection and rapid countermeasure development. To support them, we created a BioProject on the Sequencing Read Archive (PRJNA1379685) where we will upload all Zephyr sequencing reads (with human reads removed1) over the coming weeks. Further, reads that match known human viruses can be accessed via our public dashboard.

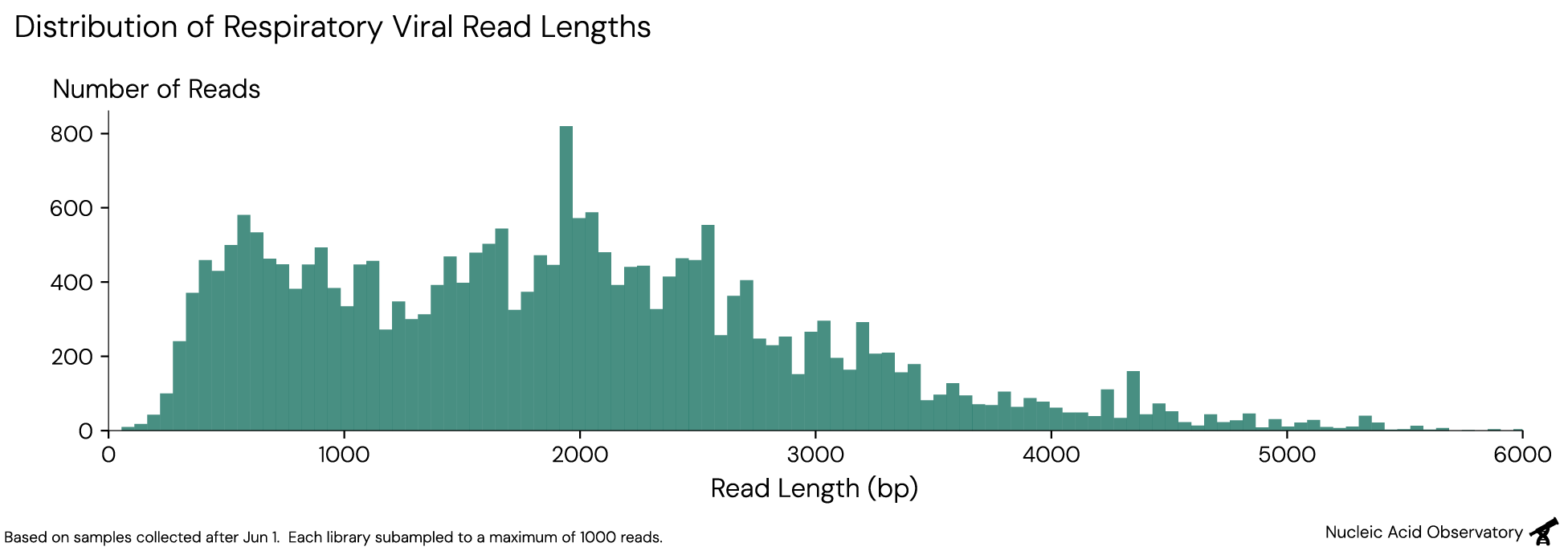

The data we make public is created through Oxford Nanopore sequencing, which generates relatively long reads: For respiratory viruses, we get a median read length2 of 1,857bp (5th% = 436bp, 95th% = 3,900), which can cover a substantial section of a typical respiratory virus genome (~7,000–30,000 bp).

Long-read data can support detection methods beyond the targeted detection methods we’re currently using. For instance, we are interested in applying de-novo assembly algorithms to Zephyr data (i.e., reconstructing genomes from overlapping reads). This pathogen-agnostic detection approach is far harder with wastewater sequencing data, which generates a much larger number of shorter reads. We hope that by making our data public, researchers worldwide might come up with additional detection methods that are well-suited to pooled swab sequencing data.

Scaling Zephyr to other cities

We believe programs like Zephyr could play a large role in strengthening public health and biosecurity in cities beyond Boston. To support such efforts, we aim to make all Zephyr resources public. This includes our approved IRB protocol, brochures and signs, computational pipelines, and wet lab protocols.

To help others assess the feasibility of setting up a comparable program, we created a simple cost model. We estimate that a system run across six months, collecting 3,400 swabs per month across five sampling days per week, with two ONT sequencing runs weekly, would cost around $630,000. We expect scaling the current Zephyr program to additional cities would involve lower marginal costs, as processing could be centralized and program management shared across sites.

Looking ahead

Zephyr is already helping us monitor for concerning known pathogens. Once we’ve collected data through the full 2025/2026 winter season, we plan to publish a detailed analysis of Zephyr’s performance and cost-effectiveness. In the meantime, if you’re interested in partnering on the Zephyr program or have questions about our data, we’d love to hear from you at nao-inquiries@securebio.org.

Footnotes

Using NCBI’s Human Read Removal Tool.↩︎

Read counts computed after subsampling to a maximum of 1000 reads for each library. Without subsampling, median read length is 2,364bp (5th% = 1072bp, 95th% = 4,195), because we tend to get both more reads and longer reads from our best-performing libraries.↩︎